Interest in tank-based shrimp production systems has been increasing in recent years in North America and Europe, while it's also slowly gaining traction in tropical regions too.

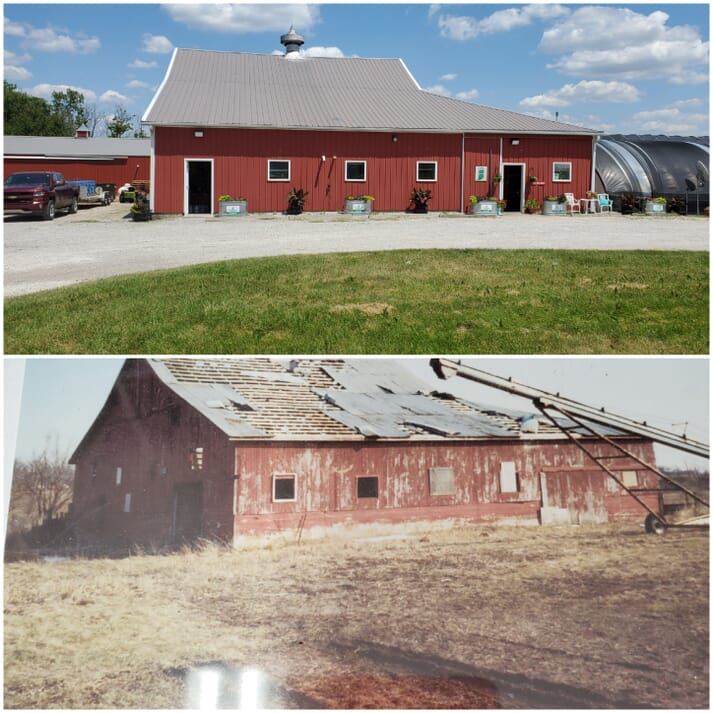

© RDM Aquaculture

Factors driving this trend include proximity to markets and the ability to offer fresh product to consumers. This strategy reduces the need for cold chain middlemen, in both developed and less-developed regions. Questions of resource availability, especially land and water (in this case brackish or saline water) have also sparked interest in tank-based shrimp farming in tropical regions. Lack of access to land for pond-based production is a real issue in many countries where conditions are otherwise suited to shrimp farming.

In both temperate and tropical regions, buildings can be retrofit from other uses, but electrical distribution and outlets must be upgraded for outdoor conditions and with ground-fault interrupt circuits. Floors can be as simple as sand and gravel or concrete with trough drains, but in temperate areas walls and ceilings must be highly insulated. Adequate ventilation is also crucial to reduce damage from mildew and humidity. In tropical regions, a building is not necessarily required, but it provides security and protection from the elements.

When considering raising shrimp in tank systems, both technical and economic factors must be addressed. Many functional configurations exist but profitability depends on capital costs, operating costs, survival and growth rates, and market conditions. Equipment options and management expertise impact both technical and economic feasibility. In North America, some successful operations are extremely limited in size, while in Europe attaining economies of scale seems to be a more important issue. To be competitive in Europe, North America and many other regions, most small-scale producers need to offer a comparatively large product (>20g average weight).

In all fairness, raising shrimp in tanks is not a novel concept. In 2004, Baron-Sevilla and colleagues published results from shrimp grow-out trials in a saltwater RAS. Their system had a total volume of 11 m3, of which roughly half was in the culture tank. After five months, they harvested slightly less than 10 kg/m3. For details, see: Ciencias Marinas (2004), 30(1B): 179–188.

© Andrew J Ray, KSU

Small-scale shrimp producers are utilising both RAS and biofloc systems in a number of countries. Harvest rates in RAS in the US typically range from 4 to 7 kg per m3 per cycle. The nursery phase for these tank-cultured shrimp currently uses 2000 – 3000 post-larvae per m3. When shrimp reach 1 gram they are moved to grow-out tanks at 250 per m3, and 80 percent survival is a reasonable goal. With more variable yields, biofloc may provide better FCR under some conditions but the RAS approach is generally more energy efficient, easier to manage and exhibits more stable water quality on a day-to-day and seasonal basis. Biosecurity has been cited as a problem in RAS, as is increased vulnerability to equipment failure and the resulting redundancy requirements.

Whatever type of system is determined to be most effective for a given operation, the same questions plague both RAS and biofloc shrimp producers. Where will the feed come from? At what cost and how often? Where will the post-larvae come from? At what cost and how often? How reliable is the electrical service? Where will the water come from and at what cost? How will salty wastewater and sludge be disposed of? The answers differ, depending on what part of the world the project will be developed.

In Indonesia, where industrial scale shrimp production is the norm, Ridwan Latif and colleagues reported earlier this year on a practical RAS for small-scale shrimp producers. When stocking 400 post-larvae per m3, they attained 70 percent survival and a feed conversion of 1.11 to 1. A benefit/cost value of 1.56 was calculated for the RAS, with an internal rate of return of 32.66 percent and a revenue/cost ratio of 1.49. For details see: https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202014701002

Dr Andrew Ray, an associate professor with Kentucky State University, has emerged as an expert in indoor shrimp production in North America. He noted: “I have a hard time understanding the status of the US industry. It’s especially hard to quantify the number and size of many of the small-scale farms popping up.” Although by no means a complete list, the 2018 USDA Census of Aquaculture reported marine shrimp farms in 13 states, including places like Colorado and Minnesota.

Although there are many unique configurations currently in operation, certain typical characteristics are emerging as the US industry grows. Some less expensive tank options, such as above-ground swimming pools, may not be sufficiently durable for long-term use, and some of these contain toxic compounds intended to prevent the growth of mildew or algae. High costs associated with ready-made fish culture tanks can preclude profitable production, but in almost any part of the world suitable tanks can be constructed in-house using a variety of local materials. If HDPE liners are available tanks can be constructed of lumber or welded wire with fitted liners. Many designs, photos and illustrations can be found online.

Energy efficient regenerative blowers and continuous electrical service are a must for both RAS and biofloc, and performance curves must provide sufficient volume for operating depths. Aeration should be sufficient to prevent solids from settling on the tank bottom and to maintain 5 ppm of DO at all times, with roughly 200 lpm of air for every kg of feed. In temperate zones, a constant temperature of 27°C represents a trade-off for heating costs, growth and reduced stress. Ground-coupled heat pumps or water heaters with closed PEX loops work well to circulate warm water through submerged hoses. Salinity of 20 ppt is also a good trade-off for water quality maintenance, shrimp health and operating costs. Salt can be mixed from various components on-site, at lower overall cost than pre-packaged mixes.

Biofloc, the alternative to RAS for small-scale shrimp production, is a management-intensive approach where a complex community of bacteria is cultured in the same water as the shrimp, providing breakdown of wastes and supplemental nutrition. Both approaches can be combined, actually, although this is not a common practice. A combination RAS/biofloc system in Indonesia, stocked at 500 PL/m3, yielded 2.7 kg/m3 at 60 days (with an FCR of 1.1, survival of 78 percent and average weight of 7 g) and 4.2 kg/m3 at 84 days (FCR 1.54, survival 70 percent and average weight 12.06 g). See: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2018.04.002

One North American operation that has been a trailblazer in tank-based biofloc shrimp farming is RDM Aquaculture in Fowler, Indiana. Vice-president of operations, Karlanea Brown, has been holding things together at RDM for the past 12 years. During that time the company has grown steadily. When asked about things she hadn’t anticipated when operations began, her straightforward answer was “not knowing how to raise shrimp.” She credits RDM’s success with designing their own systems and “learning how to manage the water”.

One advantage to RDM’s biofloc strategy is zero discharge – this allows them to avoid many bureaucratic permitting issues, and would not be possible with a typical RAS. RDM makes their own saltwater, but only when needed for expansion as new tanks are put into production. The “original” water on site is now over 10 years old, and while RDM started with two nursery tanks and six grow-out tanks, they currently operate 19 large tanks, 7 smaller tanks and 10 nursery tanks, and they plan on putting 24 more tanks into production in 2021.

RDM has advised a number of other tank-based shrimp farms in the US and other countries. While emphasising the importance of starting out small and expanding gradually, Brown explained “Once you get the water right, that becomes the key to expanding. Biofloc changes and you have to manage it. You must have patience. Many people lose patience because the cash flow is not there. Or they are not able to afford lots of employees.” To sum it up, she added “Your first year is gonna suck.”

© RDM Aquaculture

RDM has sourced its post-larvae from several hatcheries in the US (there are only a few to buy from). Sourcing P-L’s has been difficult in recent years, due to hurricane impacts on hatcheries and temporary USDA closures due to disease issues. Presently there are three potential post-larvae suppliers for US shrimp producers and RDM uses more than one, typically obtaining 70 to 90 percent survival during grow-out regardless of the source.

RDM is located, as Brown herself says, “in the middle of nowhere”. Yet most of their customers drive two or more hours to purchase fresh shrimp. The farm offers retail sales six days a week, and some regular customers drive six hours for their shrimp fix. Other than the tanks, Brown and her husband have made “pretty much everything” themselves, and they have plans to keep expanding right where they are. RDM has also begun raising oysters at their Indiana facility, in both mono- and polyculture. Current plans also include culturing freshwater redclaw crawfish as a way to offer more products to their fresh product loving customer base.

August 31, 2020 at 12:43PM

https://ift.tt/2QEXFvc

Why small-scale, tank-based shrimp production is on the rise - The Fish Site

https://ift.tt/3eNRKhS

shrimp

No comments:

Post a Comment